Table of Contents

The Blair Family and Its Wealth

John Insley Blair

John I. Blair’s Children

Ledyard and Florence Blair

Ledyard and Florence Blair’s Children

Marjory Bruce Blair

Florence Ledyard Blair

Edith Dodd Blair

Marie Louise (Marise) Blair

Blair & Co.

Developing and Designing Blairsden: Carrère & Hastings

Constructing the Blairsden Estate

The Design and Layout of the Mansion

Landscape Architect James Leal Greenleaf

Ravine Lake and Dam

The Drives to Blairsden

The Original Main Entrance Drive

The Main Street Entrance

A Self-Contained World

A Day in the Life of a Blairsden Guest

Blairsden after the Blairs

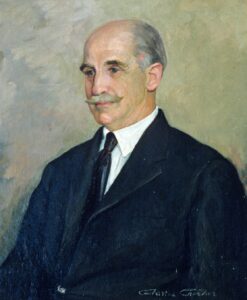

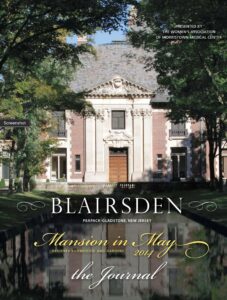

Blairsden, in Peapack-Gladstone, New Jersey, was developed as the 500+-acre country estate of New York banker and sportsman Clinton Ledyard Blair (1867–1949), his first wife, Florence Osborne Jennings (1869–1931), and the couple’s four daughters. Although the Blair family also maintained residences in New York City and, for a time, in Bermuda, Blairsden was the family’s principal and favorite residence, and all four daughters were either married or had wedding receptions there.

The estate was planned, designed, and built between 1897 and 1903, with interior alterations made to the mansion around 1912 and 1917. At nearly 50,000 square feet of living space, the four-story mansion is one of the largest, and architecturally one of the most significant, residences in the United States.

The design of the mansion, outbuildings, and the overall layout of the estate and its landscape were the result of a collaboration among the prominent New York architectural firm of Carrère & Hastings, landscape architect James Leal Greenleaf, and civil engineer Frank Stone Tainter.

Writing in his 1976 Columbia University Ph.D. dissertation about the architectural work of Carrère & Hastings, Curtis Channing Blake described Blairsden as “the finest Edwardian country house in America,” adding that, “the house along with its extensive gardens, pools, lake, farm buildings and forests stands as the apotheosis of the year-round American country residence. It is hard to imagine a more idyllic and graceful situation for the playing out of the Edwardian country life.”

From the earliest days of its design and construction to the present, Blairsden has received a great deal of generally rapturous coverage in the architectural and general press, both domestically and as far afield as Europe and Australia. For example, in 1904, within a year of the mansion’s completion, architectural historian and critic Barr Ferree gave Blairsden pride of place in the front of his influential book, American Estates and Gardens, describing the property’s landscape as “one of the most elaborate and extensive schemes of its kind ever carried out in America.”

In addition to the many written works about Blairsden, the mansion was also the setting for several scenes in the 1915 silent film, Poor Little Peppina, starring the celebrated movie star, Mary Pickford.

The Blair Family and Its Wealth

Like the Vanderbilts, the Blair family acquired enormous capital during two generations—those of John Insley Blair and his son DeWitt Clinton Blair—and spent lavishly in the third generation, represented principally by Clinton Ledyard Blair.

However, due to extravagant and conspicuous spending throughout Ledyard’s life, exacerbated by financial reverses in the 1920s, by the end of his life he had frittered away much of the enormous wealth that had been built up by his grandfather and father and he had become financially dependent on his daughters and their husbands.

Clinton Ledyard Blair was the favored grandson of John Insley Blair, a man of Scottish Presbyterian stock whose life, from 1802 to 1899, spanned the nineteenth century. Through business success, primarily in the railroad, iron, coal, mining, and land-development industries, John I. Blair became one of the wealthiest Americans in history, with a net worth at the time of his death estimated at $70 million, equivalent to about $2.5 billion today.

John Insley Blair was born at Foul Rift, an unincorporated community along the Delaware River just south of the town of Belvidere, the county seat of Warren County, New Jersey. Two years after his birth, the family moved to a farm near the Warren County town of Hope, about ten miles away.

Born into a large family of modest means and being more interested in making money than in farming, John I. Blair left school at about age eleven to work in a country store owned by a cousin. By age eighteen Blair owned his own store, and at twenty-seven was operating a chain of five general stores and several flour mills. In 1830 he and a brother organized the National Bank of Belvidere, New Jersey, which helped finance many of John’s early business ventures. Blair remained president of the bank for some sixty years.

In about 1819 John moved from Hope to the nearby Warren County town of Butts Bridge, which soon thereafter was renamed Gravel Hill. About twenty years later, in recognition of Blair’s growing business success and prominence, Gravel Hill was once again renamed, this time as Blairstown. Blair remained a resident of the town until his death.

Despite his growing wealth, and in stark contrast to many other rich industrialists and financiers of the so-called Gilded Age, John I. Blair maintained a modest lifestyle and was known around Blairstown simply as “plain John I.” According to his December 3, 1899, obituary in the New York Times, “Blair’s habits were always simple and unpretentious and his acquirement of millions made little change in his mode of living. . . . his garments were usually ill-fitting and shabby, and he looked in his walks much like a figure left over from the last century.”

Blair’s business activities expanded far beyond Blairstown. He acquired interests in the iron mines at Oxford Furnace and the coal mines of Pennsylvania, and he invested in the Scranton brothers’ Lackawanna Coal & Iron Company, one of the earliest suppliers of steel rails for the burgeoning railroad industry.

Railroad development became the primary focus of Blair’s business activities for the better part of his life. He was a key player in the expansion of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad. According to his Times obituary, “Mr. Blair built with his own capital, or with the capital of those associated with him wholly or in part, nearly thirty railroads.” At one time he was president of sixteen railroads and was reputed to own more miles of railroad right-of-way than anyone else in the world.

His obituary went on to note that, while building railroads across the west Blair secured land grants totaling nearly 2.5 million acres as premiums. To promote the economic development of both the land and his railroads, Blair formed land companies that laid out sites for many new cities and towns, many of them named for Blair and his relations and business associates.

Despite the demands of managing his far-flung business empire—for many years Blair reportedly logged upwards of 40,000 miles per annum traveling on his private railroad car—he never lost interest in his hometown. In 1848 he was one of the founders of what is now Blair Academy, a private preparatory school. He donated the land and much of the cost of the school’s first building, and until his death, remained a principal benefactor of the school.

Although not a college graduate, Blair in 1866 was elected a trustee of the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, and served on the board until his death some thirty-three years later. In the 1860s Blair funded the school’s professorship in geology, which today ranks as the university’s second oldest endowed chair. In 1897 he donated funds to build the first section of Blair Hall, the first of the university’s Collegiate Gothic-style buildings that, to a large degree, came to define Princeton’s architecture for many years.

In addition to his support of Blair Academy and Princeton University, Blair also gave significant financial support to Lafayette College, in Easton, Pennsylvania, and Grinnell College, in Grinnell, Iowa.

In politics, John I. Blair was a New Jersey delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln for president. Reportedly, it was on that trip that Blair saw the economic development potential in the western states and territories, especially across Iowa, Wisconsin, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Missouri, where he built railroads and helped establish numerous communities.

In 1868 Blair ran for governor of New Jersey, losing by a 2.5% margin to Theodore Fitz Randolph, a lawyer and businessman from Morristown.

John Insley Blair and his wife, Nancy Ann Locke, had four children, two daughters and two sons. Emma Elizabeth Blair was married to Charles Scribner, founder of the eponymous publishing house, and Aurelia Ann Blair was married to Clarence Green Mitchell, a New York lawyer. Descendants of the Scribner and Mitchell families, as well as descendants of the Blairs, all established country estates in the Somerset Hills.

John and Ann Blair’s second-born child, Marcus Laurence Blair, never married and died at age forty-four.

The Blairs’ third-born child, DeWitt Clinton Blair, was married to Mary Anna Kimball, with whom he had three children, all sons, although only two of the children lived to adulthood: Clinton Ledyard Blair and his younger brother, John Insley Blair, both of whom were generally known by their middle names.

DeWitt Clinton Blair, a Princeton graduate, succeeded his father on the university’s board of trustees, serving from 1900 to 1909. DeWitt also donated funds to expand Blair Hall to its present size and also supported Blair Academy.

Unlike his father and grandfather, Ledyard Blair did not serve on the university’s board of trustees. This may have been due to Blair’s fight with Princeton’s president Woodrow Wilson over the latter man’s reforms at the school or, years later, Blair’s objections to President Wilson having signed the Revenue Acts of 1913 and 1916 that established the modern federal income tax.

DeWitt and Mary Anna Blair lived in a large house in Belvidere, New Jersey, where their three children were born and raised. In 1923 the house was sold to the Presbyterian Synod of New Jersey. Significantly altered and enlarged, the former Blair house served as the Presbyterian Home for the Aged for nearly fifty years. Since the mid-1970s the building has been occupied by the Warren County Public Library.

Within a year or two after John I. Blair’s death, DeWitt and his wife acquired two additional homes. They built a double-wide, limestone-fronted mansion at 6 East 61st Street in New York; and they acquired, altered, and enlarged an existing estate house at Bar Harbor, Maine, that they renamed Blair Eyrie. DeWitt retained landscape architect James Leal Greenleaf, who at the same time was designing the landscape at Blairsden, to design the gardens and grounds at Blair Eyrie.

DeWitt Blair’s New York City townhouse was razed in the late 1920s to make way for the Pierre Hotel, which opened in 1930. Blair Eyrie was demolished in 1935.

In 1891, the year after his graduation from Princeton, Ledyard Blair married Florence Osborne Jennings of East Orange, New Jersey. Florence was a daughter of Catherine Almyra Dodd and Horace Newton Jennings, a partner in the New York pharmaceutical manufacturing firm called New York City Drug Mills, later the Gregory & Jennings Co.

In addition to Ledyard Blair’s business activities on Wall Street (see below under “Blair & Co.”), he was an active sportsman. He was a member and one-time commodore of the New York Yacht Club, for which his 254-foot steam yacht, the “Diana,” served as the club’s flagship.

Ledyard and Florence Blair were accomplished equestrians, both as riders and carriage drivers. They were members of, respectively, the Coaching Club of New York and the Ladies Four-in-Hand Driving Club. The latter club was organized in 1901 by Helen Benedict Hastings, the wife of Blairsden’s principal architect, Thomas Hastings.

The Blairsden estate featured several miles of coaching drives and bridle paths, as well as a riding track, and Ledyard and Florence each hosted several of the two carriage clubs’ elaborate coaching excursions from New York City to Blairsden.

Ledyard eventually turned over much of his collection of carriages and sleighs to one of his sons-in-law, Richard Van Nest Gambrill, who kept them at his nearby Peapack-Gladstone estate, Vernon Manor. Following Mr. Gambrill’s death, several of the Blair and Gambrill carriages and sleighs, including the famous road coach “Defiance” and the smaller pony coach “Defiance II” were donated by his widow, Edith Blair Gambrill, to the Shelburne Museum in Vermont. Other Blair and Gambrill horse-drawn vehicles are now in the collection of the Staten Island Historical Society at Historic Richmond Town. One of the Blair carriages that had been taken to Bermuda when the Blairs wintered there has, in recent years, been restored and is still driven around the main island.

Florence Osborne Jennings died in 1931. Five years later Ledyard married Harriet Stewart Brown Tailer, the wealthy widow of T. Suffern Tailer, who had been a friend of the Blairs. Harriet and Ledyard split their time between her Newport estate, Honeysuckle Lodge, which overlooks the famous Cliff Walk at 225 Ruggles Avenue, and an apartment they occupied at 740 Park Avenue, one of the most legendary moneyed addresses in New York City. Ledyard died at 740 Park in February 1949.

Ledyard and Florence Blair’s Children

Ledyard and Florence Blair had four children. In order of birth, the daughters were Marjory Bruce, Florence Ledyard, Edith Dodd, and Marie Louise, who was known as Marise.

In 1913 the Blairs’ eldest daughter, Marjory Bruce (1892–1975), was married to William Clark in a lavish ceremony and reception held at Blairsden. William was a son of John William Clark, president of the Clark Thread Company of Newark (the American branch of the family firm from Paisley, Scotland) and Margaretta Cameron, a daughter of United States Senator J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania who had previously served as secretary of war under President Ulysses Grant.

John William and Margaretta Clark’s country estate was the extant stone Peachcroft mansion in Bernardsville. They also maintained a twenty-eight-room Queen Anne-style brick and stone mansion in Newark. That mansion, designed by noted architect William Halsey Wood and completed in 1880, is extant as the North Ward Center.

William Clark, the son, was a lawyer and later a New Jersey and federal judge. He was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a justice of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. After World War II, Clark was appointed chief justice of the Allied High Commission Court of Appeals at Nuremberg, Germany.

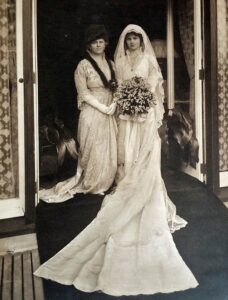

The second eldest daughter, Florence Ledyard Blair (1893–1982), was married in 1916 to Herbert Rivington Pyne, one of the five children of Percy Rivington and Maud Howland Pyne. The wedding, held at the Chapel of St. John on the Mountain in Bernardsville, was followed by a large reception at Blairsden.

The Chapel of St. John on the Mountain was built in 1907, designed by prominent New York architect Grosvenor Atterbury with funds donated by Percy R. Pyne. Originally a mission chapel of the parish of St. Bernard’s Episcopal Church in Bernardsville, St. John on the Mountain became a separate parish in 1948, about two years after the original chapel had been gutted in a fire and was rebuilt.

Percy and Maud Pyne’s country estate was Upton Pyne (later demolished), designed by James Lawrence Aspinwall of the New York firm of Renwick, Aspinwall & Owen, and built between 1899 and 1900 on the hilltop across Ravine Lake from Blairsden. The senior Pynes’ New York City house was designed by McKim, Mead & White and built between 1909–11 on Park Avenue at 68th Street. The New York house later served as the Soviet Mission to the United Nations and is now the headquarters of the Americas Society.

Herbert Rivington Pyne, following his 1914 graduation from Princeton, first worked as a private secretary to Ambassador James Watson Gerard at the United States Embassy in Berlin during the first months of World War I. He returned to the United States in February 1915, traveling on the ill-fated Cunard liner, the RMS Lusitania, which was sunk by a German U-boat less than three months later. After serving as a flight instructor and pilot in the Army Air Service in France during the war, Pyne returned to the academic world, earning a doctoral degree in chemistry from Columbia University.

Destined, however, for the world of politics, Pyne served in the New Jersey Assembly and, later, the New Jersey Senate, and was a delegate to the New Jersey Constitutional Convention of 1948. He and Florence resided at Shale, the estate they established in Bedminster, New Jersey.

In 1913, the Blairs’ third daughter, Edith Dodd (1896–1988), and her sister Marise (see below), were among a group of young people who organized the Somerset Hills Bird Club. The founder of the club was Bernardsville resident John Dryden Kuser who, the year before when he was fifteen, had privately published a book titled The Birds of Somerset Hills. For several years the club published a quarterly newsletter called The Oriole, to which Edith Blair contributed articles and served as the publication’s associate editor. Her life-long interest in birds was evident through her close friendship with Roger Tory Peterson, the naturalist, ornithologist, and author of classic field guides for birds.

The founder of the Somerset Hills Bird Club, Dryden Kuser, was a grandson of John Fairfield Dryden, a founder and long-time president of the Prudential Insurance Company and a one-term United States Senator. In 1919 Kuser married his first wife, the seventeen-year-old Brooke Russell, who became better known by her third married name, Brooke Astor.

Dryden Kuser later went into politics, first winning election as a Bernardsville councilman and then as a member of the New Jersey Assembly and Senate. While serving in Trenton his most memorable achievement was legislation naming the eastern goldfinch as the New Jersey state bird.

In 1917, Edith Blair was married at Blairsden to Richard Augustine Van Nest Gambrill, the only child of Richard Augustine Gambrill and Anna Van Nest. Edith and her husband, who was known as Dick, later established their own estate, Vernon Manor, adjacent to Blairsden in Peapack-Gladstone.

Dick Gambrill’s mother, Anna Van Nest Gambrill, who had been widowed in 1890, inherited a large fortune from her father, brother, and husband. Between 1898 and 1901, at the same time Blairsden was being designed and built, Carrère & Hastings also designed Anna’s summer estate, Vernon Court, in Newport, Rhode Island. Located on tony Bellevue Avenue, Vernon Court was designed in the style of an eighteenth-century French château. It was described by architectural historian Barr Ferree in his 1904 work, American Estates and Gardens, as “one of the truly greatest estates in America.” Sold by the Gambrill family in 1956, Vernon Court has been the National Museum of American Illustration since 1998.

Dick Gambrill, a graduate of Harvard, was a noted sportsman and coaching enthusiast, having acquired and then regularly exhibited many of his father-in-law’s collection of carriages and sleighs, including the famous Blair road coach, “Defiance.” Locally, Gambrill was master of the Vernon-Somerset Beagles and chair of the Essex Fox Hounds. He was also a director of the National Horse Show Association and the Turf and Field Club, secretary-treasurer of the United Hunts Racing Association, and served as president of the Newport Country Club in Rhode Island.

The youngest Blair daughter, Marie Louise (1899–1994), who was known as Marise, was first married, in 1919, to Pierpont Morgan Hamilton (nicknamed Pete), a grandson of financier J. Pierpont Morgan and a great-great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton, aide-de-camp to General George Washington during the American Revolution and, later, secretary of the treasury under President Washington. Following the wedding ceremony at the Chapel of St. John on the Mountain in Bernardsville, a large reception was held at Blairsden.

During World War I, Pete Hamilton served as a pilot with the U.S. Army Air Service. He enlisted again in World War II and, in late 1942, was the recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions in North Africa. Hamilton remained in the military after the war, rising to the rank of Major General in the U.S. Air Force.

Between the wars, Hamilton worked in investment banking. During much of the 1920s he and Marise and their sons lived in Paris where Hamilton was working for Morgan, Harjes & Co. While living in Paris, the Hamiltons’ sons attended the MacJannet American School at Saint-Cloud, also known as The Elms School, where one of their fellow students was the young (born 1921) Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Marise Blair and Pierpont Morgan Hamilton divorced in 1929, and on October 1, 1931, Marise was married at Blairsden to Washington Everardus Bogardus, a widower and descendant of a very old and prominent Dutch family in New York. Tragically, Bogardus, who was a banker in Hawaii, died only three months after the marriage.

Marise married her third husband, Dr. James Bethune Campbell, in 1934 in a ceremony held at Vernon Manor, her sister Edith Gambrill’s Peapack estate. During World War II, Marise worked for the American Red Cross in England.

Upon Ledyard Blair’s graduation from Princeton University, in 1890, he joined his grandfather and father in establishing the Wall Street investment banking and brokerage firm of Blair & Co. Ledyard also served for a time on the board of governors of the New York Stock Exchange.

In 1903, the same year the Blairsden mansion was completed, Blair & Co. completed the construction of its Carrère & Hastings-designed, marble-clad, sixteen-story office building at 24 Broad Street on the corner of Exchange Place, two doors down from the Stock Exchange. In 1928 the Stock Exchange purchased the Blair & Co. building. The building was demolished in 1955.

In 1920, Blair & Co. merged with another Wall Street firm, William Salomon & Co., under the name Blair & Co., Inc. Ledyard Blair became chairman of the board of the merged firm, and another prominent Somerset Hills resident, James Cox Brady of Hamilton Farm, joined the board. Ledyard retired from the firm in 1921.

In 1929, Blair & Co., Inc. merged with Bancamerica Corporation, the securities affiliate of Bank of America, becoming the Bancamerica-Blair Corporation. According to a March 22, 1929, article in the New York Times, the merger was “the first consolidation on record in Wall Street between a private banking firm and a national bank.”

Developing and Designing Blairsden: Carrère & Hastings

Seeking a country estate, Ledyard and Florence Blair in 1897 began acquiring land in the bucolic Somerset Hills. Their estate, which they named Blairsden, would eventually encompass more than 500 acres, stretching from Main Street in Peapack on the west to Ravine Lake and the North Branch of the Raritan River on the east, and from Willow Avenue on the north to Highland Avenue on the south.

To design their country retreat, the Blairs retained the services of Carrère & Hastings, at the time one of the most prominent and influential architectural firms in the country. In 1897, the same year the Blairsden project began, Carrère & Hastings won the two-part competition to design the now-iconic New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue, so Blairsden and the library were being designed and built at about the same time.

Professional partners John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings, who had both studied architecture at the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, went on to apprentice at McKim, Mead & White, the most famous architectural firm in the country, before establishing their own practice in New York in 1885.

The range and quality of Carrère & Hastings’ design work is stunning. Its more than 600 built commissions ranged from commercial structures, such as office buildings, hotels, banks, and theaters, to civic works, such as government offices and embassies, bridges and railroad stations, libraries, monuments and memorials, as well as academic institutions, churches, city and country houses, and urban planning.

One of the most significant characteristics of Carrère & Hastings’ practice, particularly when it came to the design of country estates, was their belief that the siting and design of a building must be closely integrated with the surrounding landscape. Unlike many other architects of their day, the partners’ felt that their design responsibility extended far beyond the four walls of a building and that the entire ensemble of residence, drives, outbuildings, viewsheds, as well as the hard and soft landscape elements, should be of a seamless piece.

Blairsden is a beautifully executed example of this overarching design precept. As Thomas Hastings once said, “the appropriation for a house should be divided into two equal parts, one-half for the house, the other for the gardens, pathways, court, approach, terrace and the rest of it, or, as it might be termed, one-half for the pudding, the other for the sauce.”

In light of the setting for Blairsden on a steep hill above Ravine Lake, the architects and their client opted for something of a Renaissance-inspired hilltop design. The overall architectural style of the brick and stone mansion harkens back to the reign of King Louis XIII, who ascended the French throne shortly before his ninth birthday, in 1610. Early in Louis’ reign French architectural and other decorative arts were heavily influenced by his Italian mother, Marie de Medici, who served as regent during her son’s minority. Thus, it is fitting that the Italian-influenced French architectural style of the Blairsden mansion blends so perfectly with the Italian hilltop landscape scheme that was collaboratively crafted by Carrère & Hastings and landscape architect James Leal Greenleaf.

Among Carrère & Hastings’ best-known works today are the New York Public Library and the Frick mansion, now the Frick museum, on Fifth Avenue between 70th and 71st Streets. In Washington, the firm is best known for its design of the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery and the Cannon House and Russell Senate office buildings, whose columned stone rotundas are often seen today as the backdrop for television news broadcasts.

The extended Blair family, including Ledyard’s brother, a cousin, an aunt and uncle, and an in-law, were, collectively, among Carrère & Hastings’ most frequent clients. In addition to Blairsden and the Blair & Co. office building, the firm designed Ledyard and Florence’s New York residence on Fifth Avenue at 70th Street across from the Frick mansion. The Blairs’ 70th Street house, built on the site of the former Josiah M. Fiske mansion, was completed in 1917. It was sold in 1926 and razed to make way for a luxury apartment building.

In 1914, and again in 1919, Carrère & Hastings designed alterations to Ledyard’s Trowbridge & Livingston-designed stable and artist’s studio at 123 East 63rd Street in New York. The building, which is extant, was constructed between 1900 and 1901 when the Blairs were living nearby at 15 East 60th Street, just two doors down from the Metropolitan Club of New York.

Even before the design and construction of the stable building was completed, Ledyard arranged for a family friend, portrait and figure painter and muralist John White Alexander, to locate his New York studio in the upper floors of the building.

A contemporary of John Singer Sargent and William Merritt Chase, John White Alexander rose to become president of the National Academy of Design. It is almost certain that Alexander’s 1901 oil portrait of Florence Blair was painted in the 63rd Street studio. That portrait, and Alexander’s prize-winning figure painting, Automne—which was acquired by the Blairs and hung for many years at Blairsden—were included in Alexander’s first solo exhibition that was held at New York’s Durand-Ruel Galleries in late 1902.

In 1929, at Deepdene, the Blairs’ Bermuda estate on Harrington Sound, Thomas Hastings, in one of his last commissions, designed a landmark towered boathouse (extant), as well as classical garden structures adjacent to the main residence. The Deepdene mansion had been designed a bit earlier by two other American architects, Frederick P. Hill and Herbert E. Davis.

Constructing the Blairsden Estate

The construction of Blairsden was hailed at the time as a marvel of planning and engineering. To provide sufficient space on which to build the mansion and its 300-foot-long reflecting pool, fifteen feet of the steep hilltop were lopped off. An inclined railway, complete with a wood-burning engine, was built on the backside of the hill to haul construction materials up to the work site.

Only the finest materials were used in the construction of the house—including Indiana and French (Caen) limestone; thick slate for the roof; ornamental iron, copper, and bronze, and magnificent interior finishes of stone, rare woods, tile, plaster, and even embossed leather for the walls of the billiard room.

In addition to its elaborate design and decorative elements, the mansion included many state-of-the art technological and construction features. These included full electrical service from the estate’s own generating plant, passenger and freight elevators, a steel superstructure, poured concrete floors from basement to attic, and advanced water supply, heating, and ventilation systems. Water, pumped from below the dam up to storage tanks by the stable and carriage barn serviced the mansion, filled the reflecting pool, and flowed to the many other water features of the landscape scheme. The architects also designed a passive cooling scheme of wall and floor ducts and plenums that also moved warm air through the house in winter.

Not long after the Blairs made their first purchase of land, in 1897, they altered and enlarged the nineteenth century Melick farmhouse that was located on the property. Called White Cottage by the Blairs, the family resided there until 1903 when the Blairsden mansion was completed. White Cottage remained in the Blairs’ possession for some thirty-six years, used as a guest house and, on occasion, occupied by several of the Blair daughters and their husbands and also by Ledyard and Florence when later alterations were being made to the mansion.

In 1933, about two years after Florence Blair’s death, Ledyard sold White Cottage and some surrounding acreage to Percival Cleveland Keith, known as “Dobie,” and his first wife, Martha MacDonald. With New York architect Wallace Walton Heath, the Keiths made extensive alterations and additions to White Cottage, which they renamed Windfall. During World War II, Dobie Keith, who was a chemical engineer, oversaw the construction at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, of the gaseous diffusion plant for the separation of uranium 235, a key component of the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. Windfall was destroyed by fire in December 2009.

Among the first of Carrère & Hastings’ structures to be completed on the estate were the large brick and marble stable and carriage barn that was sited on the property’s highest point (largely extant) and a large shingle-sided farm barn (partially extant).

The Design and Layout of the Mansion

In their design, Carrère & Hastings oriented the Blairsden mansion along two equally dramatic perpendicular axes: a long entrance forecourt running from west to east, and a central axis, designed and landscaped as an allée, running from the mansion down toward Ravine Lake on a southerly trajectory.

The four-story mansion was constructed of thick bearing stone and brick masonry walls supporting a floor structure of steel girders and reinforced concrete slabs. Even the attic has a poured concrete floor.

Among the many notable and dramatic architectural elements on the exterior of the mansion are the high, steeply pitched slate roofs and high brick chimneys all designed visually to reflect and continue upward the steep pitch of the hillside on which the house is sited.

The mansion is laid out in something of a modified “H” pattern. The narrower main entrance façade with its imposing carved limestone and pedimented front is at the easterly end of the forecourt with its 300-foot-long reflecting pool. The long forecourt axis is continued inside the mansion by a wide, Caen limestone-walled hallway, or gallery space, featuring two massive fireplaces and extending straight through the house from the front door to the dining room at the far end.

Off the organizing cross hall are a series of rooms, beginning with a reception room / office and “brush-up” room on opposite sides of the entrance vestibule. Continuing past the vestibule, the billiard room, with its tooled leather wall coverings, is on the left across the hall from the salon / music room. In the center of the house, overlooking the terrace, is the large living room with two fireplaces and beyond it a wood-paneled library.

Across the hall opposite the center door to the living room is a five-sided projection containing the elegant main limestone staircase. The design is that of a double-return staircase with curved side flights rising from an intermediate landing up to the second floor. The center of the staircase, in effect, denotes the beginning point of the long axis running perpendicular to the hall and continuing through the living room, across the terrace, and on down the stepped allée toward the lake.

Past the library toward the easterly end of the house was a long veranda that was later enclosed and redesigned as a morning room with wood paneling and a fireplace. The far end of the veranda / morning room led to an open-sided, roofed arcade along one side of the brick-walled garden designed in the style of an Italian-Renaissance-inspired secret garden, or giardino segreto. The arcade, in turn, led on to a high-roofed, open-sided belvedere with fireplace affording views down the hill to the lake and beyond.

Located at the far end of the main cross hall from the front entrance was the formal dining room, and off that to the north a conservatory-like breakfast room. Sometime around 1917 these spaces were altered to eliminate the breakfast room and turn the dining room ninety degrees from an east-west to a north-south axis. Redone in the Neoclassical English style of Robert Adam, the new dining room featured bow-fronted French doors leading out to the walled garden.

Doors connecting the salon / music room, living room, library, veranda / morning room, arcade, and on to the belvedere were formally aligned as an enfilade parallel to the main cross hall.

The second floor of the house was designed with bedroom suites for the family at the easterly end of the house, and guest bedrooms at the opposite end. As on the first floor, a central hallway oriented the rooms off to each side. Bedrooms had both solid and shuttered doors so that in warm weather privacy could be maintained yet air could circulate through the shutters.

There were two large skylights at either end of the house to bring natural light down to the second floor. At the family’s end of the floor the skylight was above an atrium-like sitting room, much like a central court in a Roman villa. The skylight at the other end of the house brought light into a sitting area and a secondary staircase leading to the third floor guest bedrooms.

Landscape Architect James Leal Greenleaf

Collaborating with Carrère & Hastings on the landscape design at Blairsden was James Leal Greenleaf. Trained as a civil engineer at Columbia University’s School of Mines, where he also taught for a time, Greenleaf later turned to landscape architecture, guided by, as he put it, “an unconscious feeling for the art involved.”

Greenleaf would eventually design the landscape for many large country estates in New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut. His first major landscape commission came in the late 1890s when he helped design the James Buchanan Duke estate in nearby Hillsborough, New Jersey, skillfully transforming what had been largely a flat terrain into its present series of hills and lakes. His skills as a civil engineer and his planting experience at the Duke estate again came into play as he worked with Carrère & Hastings to design and carry out the elaborate water works and planting plans for Blairsden.

In the Somerset Hills, Greenleaf’s landscape commissions also included the Wendover estate of Walter Phelps Bliss (now the Roxiticus Golf Club), the Pennbrook estate of Clarence Blair Mitchell (a cousin of Ledyard Blair’s), and Upton Pyne, the estate of Percy Rivington Pyne.

In 1918 President Woodrow Wilson appointed Greenleaf to the United States Commission of Fine Arts, where he served until 1927, the last five years of which as vice chairman. In Washington Greenleaf consulted on the landscape design of the Arlington Memorial Bridge, the grounds of the Lincoln Memorial, and the 1921 plan to enlarge the Arlington National Cemetery.

Greenleaf also oversaw the design of the American war cemeteries that were established in France and Belgium following World War I. He was also a consultant in planning landscape design elements for the national parks, most notably at Yosemite.

Among Greenleaf’s notable skills was expertise in the successful transplantation of full-grown trees. This was put to the test at Blairsden, where Ledyard Blair wanted the appearance of a well-established landscape.

According to a February 1903 article in the New-York Tribune, a grove of full-grown sugar maples, with trunks averaging between sixteen and twenty inches in diameter, heights of fifty to sixty feet, and each weighing between ten and fifteen tons, were dug up near Chester, New Jersey. The trees were transported to Blairsden by a circuitous train route to Peapack then loaded onto heavy drays pulled by teams of between eight and fourteen horses for the final ascent to the hilltop mansion site where the trees were planted along both sides of the 300-foot-long reflecting pool.

The hilltop landscape at Blairsden included many features of classical Renaissance Italian gardens. These included symmetry and axial geometry, an expansive vista, an emphasis on evergreens rather than flowers, a deliberate emphasis on contrasting sun and shade, the extensive use of water features, and the provision of a backdrop for sculpture.

Completing the landscape scheme around the reflecting pool, large boxwoods were planted at intervals under the maple trees and glazed terra cotta olive oil jars were placed along the pool’s coping. Marble busts of Roman emperors on stone pedestals were placed in front of dark-green-painted lattice fencing along one side; and at both ends of the reflecting pool antique carved Italian wellheads were fitted to spout water into the pool on which swans lazily swam.

On the terrace side of the mansion overlooking Ravine Lake, native red cedars were planted to create a formal allée leading down the hill. Going from the upper terrace to a lower terrace and then continuing down the hillside were a series of brick and stone steps and landings, including what was called a rampe douce, a French term for a gentle ramp of steps such as those seen at the Biltmore estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

In the middle of the allée, and providing visual, aural, and olfactory pleasure, the parallel sets of steps and landings were separated by a water rill, or cascade, the gurgling sound of which was somewhat disguised under low plantings. The water rill eventually flowed into a pool along an estate driveway.

Across the drive from the pool, and continuing downhill along the axis of the allée toward the lake, were another series of brick and stone steps and landings separated by ramps in which were set small, rounded blue and white stones in mosaic patterns, including fleurs-de-lis.

On the upper and middle terrace and on the landings between the steps along the water cascade were placed round-sheared bay, lime, and oleander trees in dark-green tubbed containers. In winter, the tubbed trees were all relocated to the protection and warmth of the south-facing, French-windowed orangerie located under the upper terrace.

Near the tennis courts, the Blairs built a roofed brick and lattice garden pavilion, sometimes known as a tea house. Beyond the tea house, and parallel to the tennis courts, was a large rose garden, designed with long parallel planting beds separated by pools of water and fountains, and with latticed seating areas providing shelter and views overlooking the mansion and the hills and lake beyond.

The Ravine Lake and its iconic stone dam, although key features of the Blairsden landscape and viewshed, were built by the private Ravine Association, not by Ledyard Blair.

Allison Wright Post, a son of the prominent architect and Bernardsville resident George Browne Post, wrote in his book, Recollections of Bernardsville, New Jersey, 1871–1941, “during the year 1894 the growth of the community at Bernardsville seemed to justify an effort to form a Country Club, and several public-spirited men joined in an enterprise to buy what seemed to them was real estate especially suitable for development for such club purposes.”

Those “public-spirited men” were four local estate owners, John Holme Ballantine, George Browne Post, Robert Livingston Stevens, and Edward Taylor Hunt Talmage. The four men contributed funds with which, between late 1894 and early 1895, they purchased a total of 365 acres along both sides of the North Branch of the Raritan River at an average cost of about $80 per acre. The plan was to develop a lake and boathouse in the valley and, on the hillside above, a clubhouse, nine-hole golf course, tennis courts, and other amenities.

With land for the proposed lake and country club in hand, the Ravine Association solicited additional subscribers to raise funds necessary to develop the property. One of those subscribers was Ledyard Blair who, in 1897, purchased shares in the Association and paid additional funds to purchase all of the Association’s land on the hill to the west of the river. It was on that land that the Blairsden mansion was soon to be constructed. On the opposite hillside, adjacent to the Upton Pyne estate, the new Somerset Hills Country Club was established by the Ravine Association.

With sufficient funds in hand to begin work, the Ravine Association hired Morristown civil engineer George Washington Howell to design the lake and dam. Local civil engineer Frank Stone Tainter served as the construction engineer for the project. Tainter was also retained by Ledyard Blair to design and build the driveway network leading up to Blairsden, working in collaboration with Carrère & Hastings and James Greenleaf.

The cornerstone of the dam was laid on October 1, 1898, by the eldest Blair daughter, Marjory. The youngest daughter, Marise, was born on July 1, 1899, reportedly on the day the dam was completed. As a result, it was said that Marise was thereafter sometimes referred to as “the dam baby.”

For guests of the Blairs, the anticipation and experience of Blairsden began even before they arrived at the mansion’s spectacular hilltop site. One only needs to imagine the excitement of coming as a guest to Blairsden in the early days in a horse-drawn carriage.

The estate came to have two principal, formal entrances, one off Lake Road in what is now Far Hills and one off Main Street in Peapack. There were also two, less-formal gated entrances (both extant) off Willow Avenue in Peapack.

In their design of the estate’s drives, as well as the hilltop landscape around the mansion, the creative team of architects, landscape architect, and civil engineer cleverly juxtaposed formality and informality, cultivation and near-wilderness, light and shade, and viewsheds that alternated between the narrow and linear and the wide and expansive. In keeping with an overall landscape scheme of a Renaissance-inspired Italian hilltop estate, each of the estate’s entrance drives presented visitors with the visual treat of a succession of different landscapes and views.

The Original Main Entrance Drive

The original main entrance drive, which is no longer accessible, began at the Ram’s Gate located off Lake Road across a rustic stone arch bridge over the North Branch of the Raritan River a short distance below the Ravine Lake dam. The entrance got its name from the carved ram’s head fountain that projected from a curved limestone retaining wall adjacent to a set of high iron gates. On the wall above the fountain the name “Blairsden” was embossed in block capital letters.

On the other side of the gates was a semicircular columned pergola overlooking the river and bridge.

The ram’s head, which is said to be symbolic of authority, determination, and action, is a decorative feature favored by Ledyard Blair. The symbol was used decoratively in the Blair mansion and in Ledyard’s personal crest and bookplate, even on iron firebacks.

After passing through the formal entrance gates, coursed quarry-faced ashlar walls with bluestone coping bordered the raked gravel drive. The driveway gradually rose upward on a route parallel to the river, passing above the dam and continuing through the trees along the lake.

Eventually, the drive took a gentle, sweeping turn to the west away from the lake to reveal the first, distant view of the mansion high above. The line of sight was drawn upward along a cedar-tree-lined allée in the center of which were a series of brick and stone steps and landings and mosaic ramps. The ramps were set with small, rounded blue and white stones in geometric patterns, including fleurs-de-lis.

After this initial visual treat, the drive turned again to the right, ducking back into the woods and continuing to rise higher before arriving at another turn to the left, the turn marked on the right by a wisteria-covered stone pergola overlooking the lake.

After making the turn, the drive continued upward in a straight line, crossing the hill and the cedar-tree allée at the midpoint and offering a closer view of the mansion still high above. On the uphill side, the view was of a parallel series of brick and stone steps and landings descending from the mansion. Between the two rows of steps were low plantings that partially covered a water rill that flowed down into a pool at the side of the drive. The downhill side of the drive revealed the series of steps, landings, and mosaic ramps that had previously been viewed from below.

At the upper end of this middle drive the road took another turn to the right passing along a stone retaining wall below the rose garden before arriving at the far end of the forecourt with its 300-foot-long reflecting pool leading to the mansion’s imposing entrance at the far end.

The second formal entrance to Blairsden, off Main Street in Peapack, was designed by Carrère & Hastings and constructed between 1909 and 1910, about six years after the mansion was completed. Although much of the drive up from Main Street is no longer used for access to the mansion, the route, some of the plantings, and much of the drive’s original hardscape remain.

The Main Street entrance is marked by a tall brick wall along the street, inset at regular intervals with large, rectangular dressed limestone blocks. The wall, which still exhibits some of its original ivy covering, marks the Blairsden estate’s western boundary.

The limestone-faced gate area is set back from the line of the brick wall and is marked by imposing, squared-off limestone columns topped by lidded urn-like carved finials. The columns anchored tall iron gates, remnants of which remain. On either side of the gates are matching pools, basins, and fountains, all part of the estate’s extensive systems of waterworks. Mythological Greek gods, sea creatures, shells and water plants are carved into the stone, including a mask fountain of Poseidon, who once spouted water into each basin, and the winged horse-god Pegasus, sired by Poseidon.

This monumental gateway provided a foreshadowing of the elegant final approach to the mansion that awaited visitors a mile up the drive. The route up to Blairsden from Main Street was carefully designed to showcase different aspects of the estate’s landscape and functions, and to give the visitor distinct and ever-evolving visual images, from formal and highly designed constructed elements to less formal, pastoral, and sometimes nearly wild forested views, before arriving at the mansion.

After passing through the iron entrance gates, on the left were a series of long, water-filled pools beneath large bowl-like basins.

Water originally flowed over the edges of the basins into the underlying pools, then flowed downhill from one pool to the next. To soften the hardscape of the pools and basins, and to provide shade and draw the eye further up the drive, a double allée of regularly spaced trees was planted along both sides of the pools, with a parallel row of trees planted along the opposite side of the drive for symmetry. To visually enclose the scene, a hedge of neatly trimmed privet was planted a short distance behind the pools and basins, and on the opposite side of the drive, behind the row of trees, a decorative lattice fence, painted a near-black Essex green, was set between limestone-topped brick pillars to provide a border and backdrop.

About 500 feet in from Main Street, just past the pools and basins, the drive passed through two matching sets of tall limestone, finial-topped columns. On the right, between the sets of columns, was a brick and stone viewing loggia with a red tile roof and arched openings along the front and two ends.

Between the set of columns on the left side of the drive, opposite the loggia, was a low arched brick and stone wall with a watering trough for horses that was fed by a carved, water-spouting mythological sea creature. On either side of the watering trough were balustrades behind which was a semicircular pool from which water flowed to fill the series of pools and basins leading down toward Main Street.

After passing the loggia and through the second set of columns, the scene rather dramatically shifted from the rigidly formal to a pastoral view. The drive took a slightly uphill and curved route lined on both sides by linden trees that created a cathedral-like allée providing both shade and heavily perfumed air in the early summer.

Seen to the left through breaks in the trees was an arcadian view of some of the eighteenth and nineteenth century stone and frame farmhouses and barns that pre-dated the Blairs’ development of the estate. This view—an example of the Gilded Age’s vision of country life picturesquely displayed—showed Blairsden’s well-tended agrarian side, as the property was always a working farm as well as a grand country estate.

Continuing uphill through the fields on the left could be seen the large, wood-shingled farm barn (partially extant), designed by Carrère & Hastings, that once housed the estate’s workhorses and dairy cows. The scene also provided, as it does to this day, a panoramic view of the Peapack village in the valley below, replete with church steeples.

Farther on, nestled in a small dale on the left, was the estate’s creamery (extant). The building’s thick stone walls and a constant flowthrough of natural spring water kept the milk, cream, butter, and other dairy products cool.

Next on the left, close to the drive, was another of the several farmhouses that predated the Blairs’ development of the property. During the Blairs’ occupancy of the estate, these farmhouses were primarily occupied by some of the estate’s workers and servants.

After passing the farmhouse on the left, the drive passed along a stone wall constructed of cobble-sized flints picked out of the estate’s fields. Although the wall has a decidedly rustic, English look, it also reflects an intentionally designed appearance, providing another example of the efforts that were made to balance the bucolic and formal aspects of the estate.

After making a hard turn to the left, the drive continues along the stone wall before making another turn, this time to the right, at which point the Main Street drive intersected another estate drive off Willow Avenue. The intersection was marked by a round pool set nearly flush with the ground. Originally, the pool (which is extant) featured a small fountain in the form of a cherub. Passing by this modest, yet somewhat formal pool and fountain set in the midst of farm fields, the visitor to Blairsden was given yet another hint of the formality yet to come.

The drive now left the farm portion of the estate and entered another distinct landscape, a gently curving drive through a seemingly virgin forest, with steep slopes on both sides of the road leading to the final, gradual ascent up to the hilltop mansion.

After passing a small cemetery for the Blair family’s pets on the right, the upland side of the road was originally planted with native woodland plants, including wild columbine, bloodroot, arbutus, jack-in-the-pulpits, violets of all kinds, and beds of ferns. The steep downhill side of the drive was lined with bluestone-capped fieldstone pillars connected to one another by simple wooden rails.

The drive continued through the woods on a gently uphill course, eventually marked on the right by a curved, quarry-faced ashlar retaining wall leading to two high stone columns set in a wall. The columns and wall were intended to form something of a final gateway and to partially obscure a view of the mansion until one has fully passed through to the forecourt and is able to take in the most dramatic scene of all, the 300-foot-long reflecting pool leading to the pedimented front entrance of the mansion at the far end.

The Blairsden estate was virtually a self-contained world for living and entertaining on a grand scale. The property included its own farm, dairy, greenhouses, orchards, and gardens to supply the family with food and flowers.

The estate also featured an amazing array of leisure activities. Outside the mansion itself, these included extensive landscaped walks and gardens complete with pools, fountains, cascades and water jets; wisteria-covered loggias and pergolas overlooking the lake, river, and dam; an elegant brick and marble stable and carriage barn and several miles of coaching drives and bridle paths; a horse track; a trap or skeet shooting range with its own small lodge; a two-story, stone and frame Adirondack-style boat house on the lake, and tennis courts with an adjacent brick and lattice viewing pavilion, or tea house, complete with a fireplace to warm players on cool fall days.

The interior of the mansion also included facilities for leisure activities, such as a billiard room on the first floor and, in the basement, a squash court with viewing platform, steam and massage rooms, and what was known as the “plunge,” a deep indoor swimming pool. The basement also included what was called a “sporting room,” directly accessible to the lower service court where male guests, after handing off their saddle horses to the Blairs’ grooms, could retire to smoke, drink, and socialize.

A Day in the Life of a Blairsden Guest

The Blairsden guest book reveals a who’s who of society from 1903, when the house received its first guests, to 1948, about nine months before Ledyard Blair’s death.

The first signature in the book is that of Junius Spencer Morgan, a nephew of banker J. Pierpont Morgan. Junius and his wife, Josephine Adams Perry, a great-niece of Commodores Matthew Calbraith Perry and Oliver Hazard Perry, were among the guests for the Blairs’ first Fourth of July party, in 1903.

In addition to other members of the extended Blair and Jennings families, frequent guests over the years included house architect Thomas Hastings and his wife, the former Helen Benedict, and Ledyard’s Coaching Club friends, such as Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, who died in the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915.

In interviews a number of years ago, Ledyard and Florence Blair’s eldest niece recalled a typical day in the life of a Blairsden guest.

She said guests often arrived by carriage from the Bernardsville or Peapack railroad stations. Ledyard Blair, who was a coaching enthusiast, somewhat reluctantly adopted the “horseless carriage,” and for a time signs posted at the estate’s gates emphatically warned: “Automobiles Positively Prohibited.”

Guests would be greeted at the front door by the butler and be ushered to one of the many guest bedrooms by a footman. Single male guests were usually relegated to bedrooms on the third floor. Brass holders at each bedroom door held cards identifying the room’s occupants.

In the English fashion of the day, breakfast for male guests was served in the dining room, while female guests typically took breakfast in their bedrooms.

Mornings would usually be spent in various athletic activities, such as horseback riding on bridle paths or on the Blairsden riding track; fox hunting with the Essex Fox Hounds; carriage driving; skeet shooting; boating, swimming, or fishing on Ravine Lake; playing tennis or squash; or golfing at the Somerset Hills Country Club. In the early days, horseback riding by female guests was almost always sidesaddle. Men could enjoy the facilities of the sporting rooms in the basement, including the “plunge” pool, Turkish bath, massage room, squash court, and lounging and smoking rooms. Canoes were provided for boating on Ravine Lake (photos also reveal the Blair daughters boating on the reflecting pool), and in the winter there was skating on the lake and the pool.

Lunch was often served in the tea house, or tennis pavilion, overlooking the courts and rose garden, on the verandah of the Adirondack-style boathouse on the lake, or under an awning on the terrace.

The open-sided belvedere at the far end of the mansion was sometimes used for after-dinner coffee, and it was said the Blair daughters enjoyed roasting marshmallows in the fireplace there.

Tennis matches often occupied the afternoons, sometimes with pros invited out from New York or down from the Newport Casino.

Tea was served at 4:00 p.m. in the entrance hall or in the semi-open arcade leading from the house to the belvedere (the arcade was later enclosed and remodeled as a paneled morning room). After tea, guests were encouraged to rest until the cocktail hour and dinner.

The dinner gong was rung in the entrance hall at 7:00 p.m., as guests—men usually in white tie and tails and women in long gowns—would process down the double curved main staircase to gather in the living room or, in warm weather, outside around the reflecting pool for pre-dinner cocktails.

After dinner, gentlemen and ladies usually separated for coffee or liqueurs, with the men often retreating to the billiard room while women went to the salon or music room across the hall. Later, the group would often reunite for musical recitals, sometimes featuring Metropolitan Opera stars, or for dancing or card games, although it was said all activities stopped promptly at midnight on Saturdays in observance of the Sunday Sabbath.

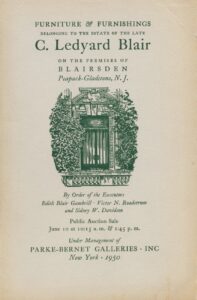

Ledyard Blair died in his 740 Park Avenue apartment in 1949, forty-six years after Blairsden was completed. The following year, New York’s Parke-Bernet Galleries sold most of the contents of the mansion at a two-day public auction held on site.

Although it has been reported that efforts were made to sell the entire estate whole, there were no takers and, later in 1950, a Roman Catholic order of nuns, now known as the Sisters of St. John the Baptist, purchased the mansion and about fifty surrounding acres for about $65,000, or about $850,000 in 2024, according to the online Consumer Price Index of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 1953, the Sisters sold twenty acres along Ravine Lake to the Somerset Lake and Game Club, which owned and continues to own the lake and dam.

In 1951, the Walter D. Matheny School (now the Matheny Medical and Educational Center) acquired acreage at the top of the hill, including the original Blair stable and carriage barn. Several other private parties, including Blair descendants, acquired other parcels of the original 500+-acre estate.

In 2002 the Sisters of St. John the Baptist sold the Blairsden mansion and its then-remaining thirty acres to the Foundation for Classical Architecture, Inc. Ten years later, the property was sold by the Foundation to Blairsden Hall LLC. In 2014 Blairsden Hall permitted the Women’s Association for Morristown Medical Center to host a Mansion in May fund-raising event in the Blairsden mansion.

Blairsden was again sold in 2022 to another limited liability company, 30 Blair PG, LLC.

W. Barry Thomson

February 2024